Tag: nellie lenora reynolds

-

Memoirs of Nona Strake, Part Three

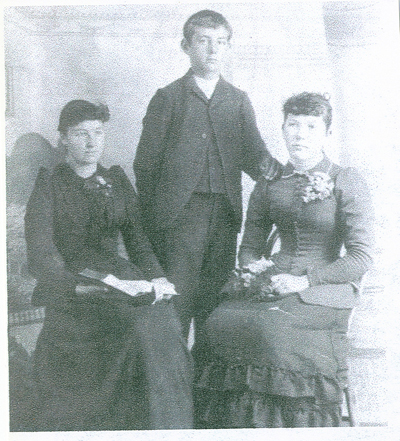

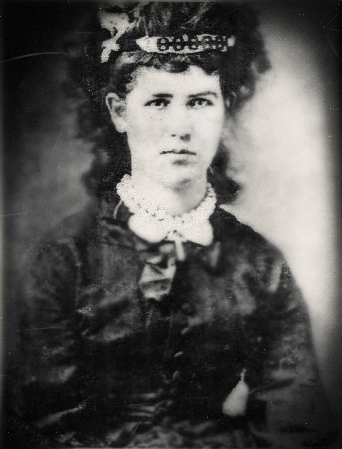

A memoir by Nellie (Nona) Lenora Reynolds, daughter of Charity Alice McKenney. Continued from part two. Both the ocean and bay beaches were full of clams of different kinds. While we were living at the Big Stump place, Bart and I used to take our small homemade wagon to the beach and dig razor clams…

-

Memoirs of Nona Strake

A memoir by Nellie (Nona) Lenora Reynolds, daughter of Charity Alice McKenney. Nellie was born 1877 April 22 in Minnetonka, Minnesota and died December 6, 1963 in Coos Bay, Oregon. Nellie first married (1) Oscar William Peterson abt. 1900 in Lincoln Co., Oregon. He was born about 1873 in Wisconsin. She married (2nd) Frederick William…

-

Memoirs of Nona Strake, Part Two

A memoir by Nellie (Nona) Lenora Reynolds, daughter of Charity Alice McKenney. Continued from part one. Most of the Indians had been taken to the new reservation on the Siletz River long before we came. A good part of the old, old sand spit upon which Waldport was built was used by them for a…

-

Nellie Strake on the McKenney Family

The below letter was written by Nellie (Nona) Lenora Reynolds, daughter of Charity Alice McKenney. She was born 1877 April 22 in Minnetonka, Minnesota and died December 6, 1963 in Coos Bay, Oregon. Nellie first married (1) Oscar William Peterson abt. 1900 in Lincoln Co., Oregon. He was born about 1873 in Wisconsin. She married…