Month: April 2010

-

Dick and I, Chapter 7, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. My thanks to Allan McKenney for sending this along. Chapter VII No breath of air to break the…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 6, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. My thanks to Allan McKenney for sending this along. Chapter VI No breath of air to make the…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 5, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. My thanks to Allan McKenney for sending this along. Chapter V ——–In religion What damned error, but some…

-

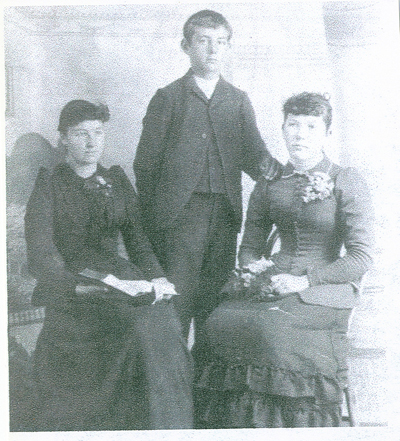

Mila Hayford, Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. and Lenore Nellie Reynolds

Mila Hayford, S. B. McKenney and Nona L. Reynolds age 14 Original courtesy of Allan McKenney. I took the liberty of retouching a bit. Mila Hayford b. 1871, daughter of Gilbert Faxon Hayford and Rebecca Ella McKenney (1848-1872), Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. (1879-1913), son of Samuel Bartow McKenney (1847-1881) and Antoinette Lagroue (1859-1880), and Lenore…

-

Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. as Child

Original photo courtesy of Allan McKenney. I took the liberty of playing around with it some. Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr., born 1879 June 10 at Whitehall, Livingston, Louisiana, died 1913 August 24 at Lincoln County, Oregon, married, 1902 June 12, in Lincoln County, Oregon, Frances “Fannie” Lorena Peek. They had four children: Clifford, Harry B.,…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 4, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. Chapter IV Are things eternal only for the dead ls there for man no hope–but this which doomed…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 3, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. Chapter III They called him back to many a glade His childhood haunts of play when brightly through…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 2, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. Chapter II But, hoply, a poor artisan Searched, ceaselessly, ’till he Found, safe asleep, the little one, Beneath…

-

Dick and I, Chapter 1, 19th Century Unpublished Book by S. B. McKenney

This manuscript was written before 1881 by Samuel Bartow McKenney. In the transcription I’ve not changed spellings or punctuation unless I absolutely must for coherence. There were no periods in the manuscript and I have added those. Dick and I Chapter I The evening wind shrieked wildely: the dark clouds Rested upon the horizon’s hem…

-

Dick and I, Unpublished 19th Century Novel by S. B. McKenney–Contents

Dick and I is an unpublished manuscript by Samuel Bartow McKenney who was born June 3, 1847 in Iowa to Robert Eugene McKenney and Mary Bartow, and was killed in April of 1881 in Whitehall, Livingston, Louisiana. An old typewritten copy was supplied me by Allan McKenney, a relation of Samuel Bartow McKenney’s who also…