Photo courtesy of Allan McKenney. I took the liberty of playing a bit with retouching and adding color.

Because the census is what we have, we tend to measure a person’s existence by where they were every ten years and what the census gives them as doing. If a family or individual happens to make a move, many imagine them going from Point A to Point B as if in a straight line. If a person is a farmer in 1870, it may be assumed they always farmed and that’s all there was to it. Whatever husband or wife is shown, it’s assumed that was the husband or wife for life. “Where did they go to church?” seems to be the next big question, and if that can be answered, into what denomination they were baptized, then from these few details a whole life is extrapolated that is a one note condensed soup.

It’s thanks to Samuel’s sister Charity, and her family’s rare inclination to preserve some of her writing and correspondence, that we begin to get at least a sketch of a life instead of a pinpoint on a map for Samuel Bartow. On January 5, 1908, from Bay View, Oregon, she wrote her niece Nellie McKenney Grasse the following:

We heard of you through your grandfather (Robert). He saw you. There was a long time we never heard from your father. Meanwhile, my mother died. That was 29 years ago the first of next month. When I heard from your father, he was living at White Hall, La. He had a wife and little boy he named after himself. (He married a French girl by the name of Antoinette Lagroue). This girl died at the birth of another child which also died, when little Bart (as we called him) was only a year and a half old. Then your father got into trouble with a southerner there by the name of Frank Williams. They had a dispute at a store in White Hall. Williams and his father in law was out in front of the store. Your father went out to talk the matter over with them. The store keeper tried to get him to take his revolver with him, but he never was afraid of anything and went out in his shirt sleeves and empty handed. He wanted Williams to settle the matter by fighting a duel, but Williams said no he would settle it by law and turned as if to go in the store, then when your father’s back was turned towards him he drew his revolver and shot him through the neck. Your father never spoke, but died in a few minutes.

Now to back up and look at the bare details gathered from assorted documents.

Samuel Bartow McKenney was born June 3, 1847, in Iowa, to Robert Eugene McKenney and Mary Bartow. Skipping the early back and forth movements of his family (which I’ll save for a post on Robert Eugene, should I get around to it), as he enters adulthood we find him in Minnetonka, Hennepin, Minnesota in 1862, enlisting with his father in Company B, the 9th Minnesota Infantry.

I find online:

Company “B” participated in Campaign against Sioux Indians in Minnesota August and September, 1862. March to Glencoe. Action at Glencoe September 3. Defense of Hutchinson September 3-4. Duty at Hutchinson until April, 1863. Moved to Hanska Lake and duty there until September, 1863.

Samuel is given as having entered as a private and ranked out as a musician.

We know from the diary of Samuel’s sister, Charity, that a prized possession of hers was an organ, that she gave her daughter lessons on it and was proud of the songs Nellie could play perfectly at the young age of six. She mentioned in her diary the procurement of a fiddle and that her husband, soon after their arrival in Oregon, had traveled to the State Capitol to see about the “school band”. So, we have here a family of musicians. Sam was a musician, as was Charity, and Charity had married a musician. It’s to be taken for granted that either their father or mother also was a musician and had passed along their knowledge of the art.

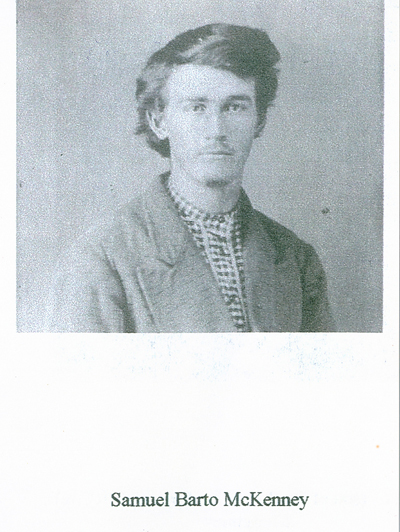

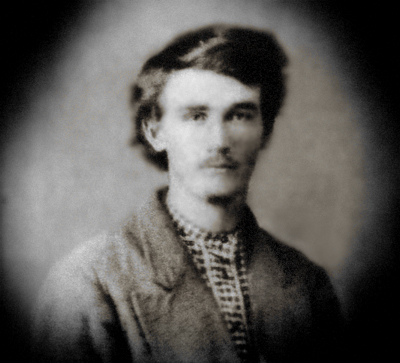

It’s difficult to tell anything about Sam’s appearance from his Civil War photo. Fortunately, we have a second, and it shows him to have been a handsome individual. Because of what is known about him, one may read in the photo a thoughtful and artistic aesthetic, but it’s likely presumptuous to find anything more than a young man with a faint line of mustache, a trace of beard on his chin, his eyes quiet and a bit distant. And though it presumes too much to read anything more into the photo, looking at it I think of youth caught up in utopian ideals that were popular for the time, less inclined to the practical than the poetic, whose spirit seeks more in the land upon which he walked than a hard currency of natural resources with which to be wrestled.

What Samuel did the following five years after the Civil War isn’t known–perhaps attending school?–but January 19 of 1868 found him in Clay County, Illinois marrying Emily O. Lewis. Circa 1869 they had a son, Ernest, in Illinois or Minnesota. They were living in Lake Mary, Douglas, Minnesota in 1870, where Samuel was a teacher.

Ernest died in 1871, in Illinois. A second son, Harold Lewis, was born September 8, 1872 in Wisconsin.

We have several samples of Sam’s writing preserved by family. The dates for two of those samples are uncertain, but the below sounds like it may have been composed while he was still in the Midwest.

SPRING TIME

Our land has been transformed as if by magic, during the last month from the desolate wastes of winter to all the verdancy of luxuriant spring.

We are no longer awakened in the morning by the merciless rains and cold shrieking wind of departing winter but are called back from the misty land of dreams by the music of singing birds and the mellow sunlight that fills our chamber with a flood of cheerfulness and surrounds all with its halo of glory. We peep from our window in the early morning and are enchanted by the dew laden flowers that shed their shower of jewels when stirred by gentle west wind. Farther on amid the green foliage we note the glitter of the river that a few days ago swept the land with tremendous and irresistible force carrying trees and houses and bridges on its turbid current; and now it goes murmuring by with a gentle ripple over the sparkling pebbles and goes dancing and laughing on its way like the happy school children that gather bluebells on its sodded banks.

Our mind is lost in the contemplation of the varied scenes of nature that spreads it beautiful panorama before us when we are called back to our home ties by the sweet voice of our loved one wooing us to the wood pile and informing us in a shrill pipe that the water pail is empty.

The beautiful scene looses all vestiges of enchantment and the sombre clouds of discontented come back, and threatening on the horizon .

Some time between 1872 and 1874, Emily and Samuel parted ways. Harold was about two years of age when Emily married John Davenport Brown on October 6, 1874 in Lena, Stephenson, Illinois. John Davenport Brown was 31 years her senior. The 1880 census in Rush, Jo Daviess, Illinois shows five children from a previous marriage living in the household, including John Davenport Brown Jr. who was 28, only four years younger than Emily. One imagines that either Emily was, at this point, eager for financial security and fed up with youthful husbands, or John Davenport Brown was an exceptional individual.

Samuel was back in Minnesota in 1875 where he married Ella Adelaide Fryer on June 20, in Genoa in Olmsted County. On March 10 in 1876 their daughter Nellie Leona was born at Genoa. Then, on April 22 in 1877, a son was born, George (Bob) Ellis. Though in Minnesota, Samuel was apparently already out of touch with his birth family, if his sister Charity had been unaware of Nellie’s birth. And probably George’s as well.

It’s probable that in 1877 Samuel was already separated from Addie, who never did remarry. He was by that year writing articles for the Bay St. Louis Herald which was published out of Mississippi.

Who knows, perhaps it was about this time–perhaps earlier–that Samuel penned the following, which looks like a sketch for a story or book. The formatting was all messed in the transcription I received but an inexact guess can be made in trying to separate the characters.

Dick and I

Dramatis Persona

The Narrator or the supposed writer is Dr. Constant Etheridge Science, a physician who attends Richard Rashboy in all his sicknesses and although his nostrums are sometimes bitter they are efficacious in giving him renewed strength and vigor. He is also the friend as well as the physician and is of great service to him in assisting him to obtain his lady love, Althea.

Richard Rashboy alias Peregrine–Liberalism. A stranger that seeks shelter of Rufus Sylvester Woolsey an inn keeper and is re(?) but is taken in by Constant Etheridge and instead (?). He falls in love with Althea. Is the friend of Bertie alias Lily and of Etheridge. Is the enemy of Adams and the Rector and is particularly disliked by Ursula Whipple.

Hope–Aleathea–Truth, a very retiring maiden and orphan and or waif.

The Ward ——– ( Reason ) The heroine of the book is beloved by Dick who after many mishaps succeeds in winning her.

Inez – Helen – Light – the sister of Aleathea, beloved by Etheridge Science.

Irene Hughes – Peaceful mind – a beautiful maiden who leaves her fathers home and disappears. The Rector, her father, prays for her to come back. She was the light of his home but she returns not. Dick and I seek her often and sometimes find her but often fail of finding her. She has taken up her residence with some simple kind-hearted people with whom Charity McDonald also resides. Left her father on account of his stern———

Reading this, I’m reminded of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s, “The House of the Seven Gables”. There’s a fair amount of wit, and one may wonder if the book was to be a satire, but I instead think that what was intended was a work of romantic, philosophical introspection softened with satirical elements.

Or was it instead a brief cipher of his own life, never intended to be formed into a novel or story?

Dick and I seek her often and sometimes find her but often fail of finding her.

A story about a physician and his patient who seem one in the same person. Together they seek but fail to find peace of mind.

UPDATE: I’ve since this writing received the manuscript of “Dick and I”, it was a novel, and will be scanning and placing it online. Am looking forward to “publishing” it!

By the time of the 1880 census, Samuel was listed with physician as his profession. During the years in which we’ve little information on him, he had studied to be a doctor.

He was also in deep trouble. There had been charges of bigamy. I’ve no information on who made these charges or in what state. What we do know is there were more women in his life than Emily Lewis and Ella Fryer. After all, Emily Lewis had herself remarried before Samuel wed Ella. Somewhere, there was at least one other marriage, which was unlawful. Sam’s duplicity was discovered. He fled.

Sam’s family, and so many of the time, were going west, further west. For all we know, Samuel may have traveled extensively and been to the western and eastern boundaries of the continent, perhaps further, before deciding to travel down the Mississippi River to Louisiana.

On August 9 1878, in Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, Samuel married Antoinette Lagroue, whose Lagroue grandparents had been wealthy plantation owners before the Civil War. A son, Samuel Barto McKenney Jr. was born June 10 1879 in Whitehall, Livingston, Louisiana.

Whitehall is in Bull Run Swamp which was as good as an entirely different country to Samuel, who had grown up in Ohio, Iowa and Minnesota.

Sam is recorded as having written the following personal reflections on his birthday in 1877, but I think a transcription somewhere along the line was in error and instead it was written in 1879, when Sam was 32 years of age:

My 32nd. Birthday

The last year has rolled away

Into the dim and shadowy past

Just such a fool

Just such a fool

God deliver em from such a foolThirty second Birthday

Exiled from home by friends forgot

In all this world there is no spot

That I may call my home or where

I can find a refuge from that care

Who has fixed in lines naught can erase

His seal and signet on my face

The 1880 census shows:

1880 LA, Livingston

Samuel B. MCKENNY 34 OH Doctor PA OH

Antoinette 21 b. LA parents b. LA

Samuel B. son 1 b. LA parents b. OH and LA

The census also shows this on page 164A:

117 Frank WILLIAMS 29 LA father Prussia mother Baden peddler in skiff

Henry E. 16 brother swamper

Josephine 19 sister

Sophie 9 sister

118/118 Henriette LAGROUE self S Female 25 b. LA parents b. LA

Alice MCKENNY Dau S Female W 6M b. LA father b. OH mother b. LA

Sam had a son with Antoinette Lagroue in June of 1879. Only six months later, in December of 1879, he had a daughter by Antoinette’s sister, Henriette (also known as Harriet).

We see living beside Henriette the man who would later kill Samuel.

About December of 1880, Antoinette died with the birth of a second child, who also died. Perhaps, after this death, Samuel lived with Harriet. In November of 1881 they had another child, Alden Leo. But Samuel was long since dead. Shot by Frank Williams in April of 1881 when Harriet was perhaps a couple of months pregnant.

I first imagined that Frank Williams perhaps loved Harriet and was angry with Samuel over her plight. But Frank Williams was married by now. On June 23, 1880, in Livingston, he had wed Palmyne Cornet. In 1880, before her marriage, we find Palmyne living several households from Samuel McKenney. Her father owned a sawmill. Frank William’s sister, Emma, was a servant in a neighboring house.

Source Citation: Year: 1880; Census Place: , Livingston, Louisiana; Roll T9_456; Family History Film: 1254456; Page: 162.2000; Enumeration District: 138; .

82 Samuel B. McKenney

…

85 Opdenmeyer William C. dealer in something (illegible) Prussia parents b. Prussia

Mary W. 38 France parents b. France

John W. 16 LA

Louisa M. 13

Frank 11

William 8

Charles E 2

WILLIAMS Emma 18 LA father Prussia mother Baden

86 CORNET Pierre Louis 60 owner of sawmill b. France parents b. France

Palymyra 53 b. LA parents b. LA

Caliste 24

Palmyra 21

Algea 17

Camelite 16

Laura 12

The 1900 census shows that Palmyra had her first child with Frank in July of 1881–and they had 7 children after that.

Return to the Louisiana storefront before which Samuel McKenney and Frank Williams and his father-in-law are standing moments before Samuel is shot to death. Henriette is about two months pregnant and likely would have known she was pregnant. Frank Williams’ wife is about six months pregnant. There is a disagreement with enough at stake that Samuel has proposed a duel that may leave Frank Williams’ pregnant wife a widow, or Henriette no support for her daughter and the other child now on its way.

It’s said that Henriette and Samuel married in Livingston Parish, but I find that doubtful as Henriette, at least in the census, appears to have never gone by the name of McKenney.

What had happened? What was the strife? Frank is enraged. His father-in-law is present. Sam proposes a duel. Frank says he will go instead through lawful channels, then shoots Sam when he turns his back.

Dueling was made unlawful in Louisiana as early as 1722 but remained popular for many years.

There were very firm rules laid down for duelists. Only the planter class fought duels. No planter would lower himself to fighting a duel with a man of lower status. Until the Civil War there were very few men in public life who had not fought a duel.

“Life in Antebellum Louisiana” by Sue Eakin, Marie Culbertson

Why in the world would Sam propose a duel?

If Frank went to prison for the shooting of Samuel, he wasn’t incarcerated very long, as his children with Palmyra are spaced at even intervals through the ensuing years.

Continuing with the letter with which we opened this post, the one Charity wrote Nellie, Sam’s daughter by Addie Fryer:

There were 15 persons present when he was killed (Sam). One man was so mad he ran to the store for a gun and followed Williams to the river and would have killed him, but there was no load in the gun and before he could get it loaded Williams was gone. The man was arrested, but was let out on $1,500 bail. You know down there in the south there is not much law.

One witness was Levi Brown of Whitehall. Another was Robert Binifeld, a resident of Maurepas, La. They saw the body of S.B. McKenney after he had died and had served as witness in behalf of the state of Louisiana.

Samuel Bartow McKenney was dead. He left behind Harold “Harry” Lewis McKenney, about 13 years of age, son of Emily Lewis; Nellie Leona and George Ellis, about 5 and 4 years of age, children of Addie Fryer; Samuel Barto, about 3 years of age, son of Antoinette; Henriette’s children, Alice, about 2 years of age, and Alden yet to be born.

By 1900, in Grays Harbor, Chehalis, Washington, Samuel’s son Harry, by Emily, was a business partner with Bart McKenney, Samuel’s son by Antoinette.

1900 Washington, Chehalis County, Grays Harbor

38/38 HITCHINSON George head 1845 55 b. Canada (Eng) father b. Scotland mother b. Engliand

MCKENNEY Harry C. partner 1872 27 b. Wisconsin father b. OH mother b. NY

GALLON Andrew partner 1858 41 b. Canada (Eng) parents b. Canda (Eng)

FAIRCHILDS Geo partner 1869 31 b. MI parents b. PA

FLANAGAN Chas. partner 1880 19 b. MI father b. Unknown mother b. IN

MCKENNEY Bart partner 1879 20 b. LA father b. OH mother b. NY

CARR Geo T. partner 1864 36 b. CA father b. Ireland mother b. NJ

By 1920, Harry was living in Beaver, Lincoln, Oregon, the county were Samuel’s sister, Charity had moved in 1883, and where he had a large number of extended family. He later moved to Estacada in Clackamas then Southwest Condon in Gilliam County.

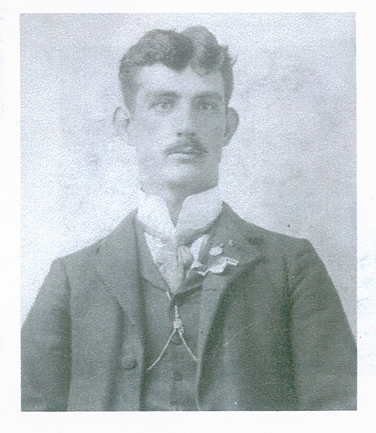

We have a photo of George Ellis McKenney, Samuel’s son by Addie Fryer.

Fryer and Phelps families. George Ellis McKenney and Addie Fryer McKenney are on the far right. Photo courtesy Allan McKenney.

George became a miner and stayed, for the most part, in Minnesota. His sister, Nellie Leona, married in Minnesota and also made her home there.

Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr., after his father’s death, went to Minnesota to live with his aunt Charity and her husband Al Reynolds.

The below photo is given as being Sam McKenney Jr. at the age of 3 and shows his French Louisiana origins. He’s impeccably dressed in clothing that would have been alien and strange in Minnesota, and though it’s noted the photo was made in Minnesota, I wonder if instead it was done at a studio in Louisiana.

Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. age 3. Photo courtesy Allan McKenney.

Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. traveled to Oregon in 1883 with his aunt’s family (she noted in her 1883 diary how he still sometimes spoke French) and remained in Oregon and Washington the remainder of his life, which wasn’t a long one, he dying at about the age of 32.

Samuel Bartow McKenney Jr. Photo courtesy of Allan McKenney.

And what of Henriette and her children, Alice and Alden? What kind of life would be allotted a woman who had two illegitimate children by her sister’s husband? They’d been the granddaughters of a plantation owner worth $50,000 at the start of the Civil War, a considerable amount, but I find nothing on her Lagroue grandparents and father and mother after the Civil War. I don’t know where they were in 1870. I don’t know if the family had lost everything that they’d built on the slavery plantation system, or if they retained some social standing and wealth that filtered down to their daughters. What would have been the psychological and social pressures, living with two illegitimate children in the Deep South? Were the children openly illegitimate or were they presented as legitimate, and on the surface accepted as legitimate? What were their social and financial hardships? Henrietta appears to have stayed in the Livingston and Tangipahoa areas (she had sisters in Tangipahoa) and it seems it would have been impossible for her to conceal her history, especially after Samuel McKenney was famously shot.

My guess is hers was a damn difficult life.

The 1880 census shows Henriette living familialy isolated, not in the proximity of any known relations other than her sister Antoinette who was in the same county. We know that she and her children were known by the McKenney family and that Charity Alice McKenney sent her shoes in the year 1883, which is perhaps indicative that Henriette was financially struggling.

Henriette never did marry. The 1900 census finds Henriette Lagroue, given as widowed, in Charity hospital. Her daughter, Alice, had just married, as Alice Lagroue, in Tangipahoa parish. Her son Alden was living, as Alden or Alvin McKenney, in the household of his aunt Charity Alice in Alsea, Lincoln, Oregon.

By 1910, Henriette was living in the household of her sister Arsene Booth, in Ward 6, Tangipahoa parish. Alden was back in Louisiana where he went by the name of Alden Lagroue. He was in prison.

Source Citation: Year: 1910; Census Place: Police Jury Ward 7, West Feliciana, Louisiana; Roll T624_535; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 154; Image: 354.

Louisiana State Penitentiary

Lagroue Alden m w 28 married twice 3 yrs. B. LOA father b. Minnesota mother b. LA laborer convict

Alden had already been married two times. I know nothing of those two marriages. By 1917 he was in Holbrook, Multnomah, Oregon for his WWI draft registration. I don’t locate him in 1920. He was back in Louisiana in 1924 where he married again–whether it was a third marriage or he had been married even more times before then, I don’t know. He was in Foley, Tillamook, Oregon in 1930 and died in Chathlamet, Wahkiakum, Washington.

By 1920, Henriette was living in Lake Charles, Calcasieu, Louisiana, in the household of her daughter Alice Reid, who gave herself as widowed but had actually been divorced from Henry Reid, a sheriff in Lake Charles, in 1919.

Henriette’s tombstone provides a clue as to how she may have presented herself to others. She is buried beside her daughter Alice. Alice is given as Alice Lagroue Mauldin and Henriette is Henriette LaBouef Lagroue. It’s my guess that though Lagroue was her birth name, she represented it as her married name and gave her maiden name as LaBouef, which was her mother’s maiden name. Though Alice McKenney is seen in the 1880 census as McKenney, later years, in Louisiana, she probably did as her brother Alden and went by the name Lagroue. Alden, when out west with the McKenney clan, went by the name McKenney, but in Louisiana, he appears to have gone by Lagroue.

What’s interesting to me is how these families of Samuel Bartow McKenney weren’t entirely alienated from each other. Indeed, as adults, Harry and Alden went to Oregon where their Aunt Charity and half-brother, Samuel, were living. Two were even involved in a business partnership. What held at least some of these siblings together as a family when Samuel counted himself as one exiled from family and friends? Was it Aunt Charity? Their grandfather, Robert? Had he taken an interest in these grandchildren that was conferred upon Aunt Charity?

Because we’ve no commentary from the children or wives, they fade into the shadows. They died much more recently than Samuel Bartow McKenney, but as a few paragraphs of his thoughts were preserved, though there is no way we can know him, he stands to the fore, musing upon the beauty of the land, of the dreariness of the mundane demands of life that siphon away a lyrical, spiritual appreciation of one’s surroundings, of his exile from friends and family, his counting himself a fool, and his search for an elusive peace of mind which it’s doubtful he ever found, at least not to his own taste. He only lived to the age of 33 and sometimes much can happen in one’s later years that alters and refines what one esteems as peace of mind, what one expects of it, but Sam didn’t have the opportunity to experience this stage of life. I partly wonder, when Samuel stepped out to talk with Frank Williams, if it was bravery or carelessness that caused him to leave his revolver behind though he was encouraged to take it with him. Did he think, leaving his revolver behind, that action might defuse the situation? Or was he gambling with fate? Was he weary of being without a refuge?

As one hundred percent confidence fails ever to be the property of any mind, a likely scenario would have both bravery and carelessness causing him to disregard his revolver when he stepped outside to address Frank Williams and Williams’ father-in-law.

Thanks to Allan McKenney who has provided Sam’s writings and Charity’s letter on Sam’s death.

Leave a Reply