The University of Missouri Press publishes some fine books. The following bio on Walser is from the Dictionary of Missouri Biography by Lawrence O. Christensen. The following is from the Google display of the book which has “permission of University of Missouri Press. Copyright.”

* * * * *

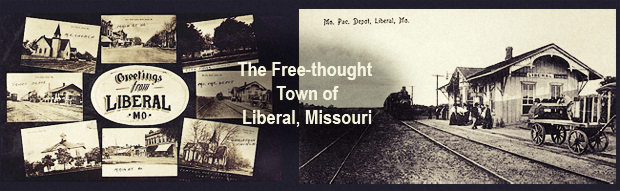

WALSER, GEORGE H. (1834-1910)

George H. Walser was born in Dearborn County, Indiana, on May 26, 1834, and died in Liberal, Missouri, on May 1, 1910. In 1856, he was admitted to the Illinois bar. Five years later he responded to the appeal of President Abraham Lincoln and volunteered for service in the Union army. He reenlisted for three additional years. By the end of his Civil War service Walser had reached the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Twentieth Illinois Volunteers. When the war was over he moved to Barton County, Missouri, to begin the practice of law in Lamar.

As a Republican Walser entered Barton County politics and served as the county superintendent of schools and the prosecuting attorney. In 1868 he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives where he served two terms. In the area he was known as an effective trial lawyer.

Although Walser was born into a Christian home, he became increasingly critical of the faith after the Civil War. He as particularly impressed with the books and speeches of Robert G. Ingersoll who mesmerized crowds with his eloquent defense of agnosticism and converted many Americans–outraged others–with his writings, such as “Some Mistakes of Moses” or “Why I am an Agnostic”. Walser became convinced that he should take up the challenge of establishing a free-thought community. In 1880 he bought land in western Barton County, platted a new town that he called Liberal, and began publicizing his development.

Walser in the 1880s must have been a bundle of energy as he developed and directed his new community, which had eight city blocks, twenty-five business lots, fifty-seven residential lots, and a city park. (From 1887 to 1889 the estimates of the population of Liberal varied from five to eight hundred.) Walser continued to practice law. He established and published a newspaper called The Liberal. He operated a coal mine. He built a hotel for the community, the National Hotel, which was advertised as operating on “a liberal basis.” He was the founder of Freethought University in Liberal, and the catalog identifies him as the teacher of commercial law. In addition, he found time to write for the magazine the Orthopaedians and also published three volumes of esoteric poetry–full of classical allusions.

Among his other activities, Walser developed a cemetery at Liberal and, of course, sold lots. When he died in 1910 his fourth wife, Esther Jaemison Walser, made the unusual decision not to bury him in his own cemetery. Instead she had the body interred in Lake Cemetery at Lamar.

In the history of Missouri, Walser stands alone as the developer of a community that emphasized that religion was not welcome in the new town. He was vocally anti-Christian, and described Liberal in these words: “We have here neither priest, preacher, justice of the peace, or other peace officer, no church, saloon, prison, drunkard, loafer, beggar or person in want, nor have we a disreputable character. This cannot be truthfully said of any christian town on earth.”

Liberal was distinctive because of its free-thought ties. For example, they used a different dating system. Instead of utilizing the supposed date for the birth of Jesus Christ as the base for their system, they used the year 1600 A.D., to honor Giordano Bruno who that year was burned at the stake by the Catholic Church for his freethinking. Thus, the year 1882, using their system, was called E of M 282 or Era of Man 282. Such a dating system had been recommended by the National liberal League.

Freethought University, which appears to have begun operation in 1886 or 1887 in Liberal, was established to provide a place where freethinkers could confidently send their children. The catalog described it as “the only institution of learning in America that is absolutely free from superstition.” Walser was intent on making Liberal a community where freethinkers would feel comfortable. In his own words, “Liberals should come here because it is the only established Liberal town in the world with institutions for promulgating the ideal advancement of liberated minds.”

Conflict erupted between freethinkers and Christians in Liberal in the 1880s. William H. Waggoner platted and began building an addition just north of Liberal in 1881. He let it be known that he hoped Christians would flock to his settlement. Walser then constructed a high barbed-wire fence to keep Christians out of Liberal. For two years there were verbal exchanges along the barbed-wire fence. Finally in 1883, Walser bought out Waggoner, and the conflict ended.

The declining support for freethinking led to a surprising development in 1889. Walser announced the sale of a plot of land and the Universal Mental Liberty Hall to the Methodist Episcopal Church for the sum of $485. The hall was to be used as a Methodist Sunday school. Its sale marked the end of the freethinking movement in Liberal, less than a decade after the settlement’s founding.

It is interesting to note that in 1889 when the free-thought movement in Liberal ended, a new religious movement, the Spiritual Science Association, was gaining prominence in the town. Spiritualists encamped at Walser’s Catalpa Park in July and August each year until 1903 by which time spiritualism in Liberal also had waned…

Duane G. Meyer

Sources listed are the Lamar Democrat, 18880s.

Liberal Mo. Promotional Booklet. Item H1481.35 W168L. State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia.

Meyer, Duane. The Heritage of Missouri. Springfield, Mo: Emden Press, 1993.

Missouri: The WPA Guide to the “Show Me” State, St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1998.

Moore, James Proctor. This Strange Town: Liberal, Missouri, Liberal, Mo: Liberal News, 1963.

Leave a Reply